Amanda Bickerstaff was as far away from the Bronx as you could imagine.

It was 2019, and the ed-tech CEO was leading a professional learning services company in Melbourne, Australia, and was tasked with spinning its service model into a tech-driven offering -– as well as finding the funding to do it.

Transforming the company and raising funds to do it would be the biggest challenge she faced since leaving her job as a biology teacher at a struggling public school in the Bronx 12 years earlier. It was there she saw some of the system’s most pressing problems firsthand and was driven to make a larger impact in the teaching and learning space.

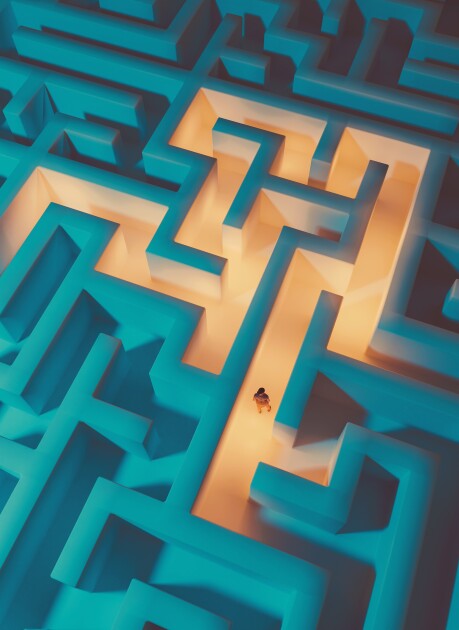

But now she was up against a brick wall.

Bickerstaff wasn’t just a CEO who happened to be a woman, she was the CEO of a company with three founders who also happened to be women. And all four of them came face-to-face with the real-life experience often represented by stark statistics, like the fact that only 2 percent of venture capital in the U.S. went to all-female founded teams in 2023.

The team faced the same dynamics in Australia, where just 4 percent of smaller-scale venture activity was directed toward solely women-founded companies in 2023, per a state of the industry report. At the time Bickerstaff was raising funding in 2019, the figure was less than 1 percent.

Women in the education sector are outnumbered in leadership positions by their male colleagues. In the first story of this two-part series, EdWeek Market Brief explored the hurdles women face in attempting to rise through their organizations, and how some executives have overcome those barriers.

But the challenges for women in the education industry don’t end when they reach the C-suite. Many also say they face difficult odds — and in some cases, open skepticism about their leadership abilities — during the critical process of attempting to raise capital necessary to grow their companies.

This story explores the fundraising journeys of women in leadership positions of education companies, and how they broke through.

Prying Open Doors

Bickerstaff had grown accustomed to what she viewed as patronizing comments and dismissive attitudes from investors. One potential funder made a point to critique Bickerstaff’s leadership after getting a glimpse of her packed schedule.

“He said, ‘Well your calendar is really messy, that’s a sign of a disordered mind.’” Bickerstaff recalled. “This is someone who was going to invest. I was just so taken aback.”

The same potential investor also predicated a minor $50,000 investment on the company making major operational changes, she said.

Despite the headwinds women entrepreneurs face in raising capital, manyfounders have risen to leadership positions in the K-12 industry, achievements that some of them, like Bickenstaff, trace in part to the foundational understanding of schools they gained as classroom educators.

The outlook for women founders trying to raise funds to fuel those ideas however, is at risk. Across all industries, the percentage of women securing venture funds has dropped to just 2 percent in 2023, the lowest it’s been since 2016 according to Pitchbook, erasing small gains seen during the peak of tech funding boom in the late 2010s. Nearly 21 percent of funding went to teams with both male and female founders, and the rest went to solely male teams.

Overall, the education industry is experiencing a dramatic contraction in venture capital funding, with total dollars invested dropping to $1.8 billion globally — the lowest fundraising total in a decade —down from $3 billion in 2023, according to the research firm HolonIQ.

The landscape has also grown more difficult because districts across the country are slashing budgets to meet financial shortfalls after federal ESSER funding ends, leaving them with far fewer dollars to spend on startups’ products.

The end result? An education industry where many of the people who have a deep understanding of its most pressing problems and innovative ideas about how to to address them have fewer avenues than their male peers to bring those solutions to life.

The Bootstrapping Option

Anne Spear is in the thick of it.

As the CEO and Founder of Plan Forward – an early-stage startup that works to help small K-12 districts develop, execute, and track strategic plans — she has bootstrapped her company to a point where she’s found product market-fit. Reaching that milestone is often a prerequisite to securing funding from ed-tech investors – and for Spear, it’s now setting the stage for a funding round in the near future.

She’s also going into the process fully aware of the obstacles that women face in securing investor support. As an academic researcher, Spear has studied gender and education, and gender and leadership, and knows the statistics well.

“There is deep, deep structural racism, sexism, and ageism in the startup space,” she said, pointing to data on the small portion of VC funding going to companies led by women.

Spear, who helped build out education research and consulting firm Hanover Research’s strategic planning advisory business, created Plan Forward after she saw how difficult it was for the small districts to afford to create accurate, evidence-based strategic plans and implement them effectively.

“There was literally an ‘Aha!’ moment when I was trying to think of how to better facilitate bringing in data into [district strategic plans] so that they were more accurate, and I just realized that technology could do it,” she said.

She launched the company in the middle of this year with less than $35,000 in working capital. The progress the startup has made in securing district clients means she’s set to not only break even, but exceed her early goals.

“That’s huge, especially because we’re very much a product that is priced to small districts,” she said.

Reaching those goals, however, has required exhaustive work and sacrifices on behalf of her team, Spear said, and she’s looking toward fundraising as a way to create a more sustainable operation moving forward.

“Financing can often feel like a short-term problem, but it sets up who you are, the product you’ll have, and the type of company you’ll be. So we are very diligent about that,” she said. “We are a fierce team. We are not a desperate team.”

It’s exhausting when you’re a woman in a leadership role. You’re walking a balance beam. There’s no right way to be.

Lakshmi Balachandra, Babson College professor

While she knows raising money in ed tech can be a struggle for any company founder, she said she has experienced and understands the “-isms” in launching a company. But she chooses not to focus on them.

A close mentor of Spears once told her that she didn’t know what a room full of men thought of her when she walked into a room – and she didn’t care.

“‘I walk into the room, and I’m myself. And that’s worked for me,’” Spear recalled the woman saying. “I’ve adopted that.”

Lakshmi Balachandra, a Babson College professor who studies entrepreneurship and its intersection with gender, said women founders are expected to mimic male behavior traits throughout the pitching process, such as having a more forceful personality.

At the same time, women can’t be seen as coming across as too inflexible or demanding, she said.

“It’s exhausting when you’re a woman in a leadership role,” she said, adding that the experience is twice as burdensome for women of color who face another layer of bias, whether explicit or implicit. “You’re walking a balance beam. There’s no right way to be.”

Tougher Era for Ed Investing, Overall

The venture capital ecosystem in the ed-tech space is in the middle of a shift post-pandemic — one that could challenge the growth of early-stage startups and efforts by women founders to secure capital, investors in the space said.

Generalist investors that entered the space during the Covid-era, attracted by low interest rates and districts’ desperation for tech-centric tools, are now exiting, many after being burned by overpaying for overhyped startups that didn’t deliver on their lofty targets, said Amy Nelson, managing partner at education-focused VC firm Rethink Education.

In some ways, that shift is good news for ed-tech specialist firms like hers, she said, since they’ll be able to ink deals without having to lure founders with unrealistic valuations.

Yet because experienced ed-tech investors better understand typical outcomes and are going to be disciplined about how they deploy their funds, that could tighten access to capital, overall, including for companies founded by women.

There will be good companies that “are going to be capital-starved and may not be able to make it, particularly those that are looking to raise sort of subsequent growth equity,” Nelson said.

It can help when women like Nelson are making decisions about which education investments to support.

The more women who are making investment decisions, the more women-founded companies that get funded, research shows: A Kauffman Fellows report released a few years ago found that women investors are twice as likely to back female founders

Many women leading education-focused VC firms arrived in those positions via the teacher-to-entrepreneur pipeline. The education industry stands out among other tech-centric fields when it comes to gender parity due in part the large number of women who begin their education careers in teaching. Investors and entrepreneurs in the space said dominance of that workforce creates a large pool of potential female company founders, who in turn can set out on the path to take roles as entrepreneurs, CEOs, and then post-exit, investors.

About 39 percent of the founders CEOs in Rethink’s portfolio are women, she said, and they are “continuing to see and speak with many very strong women CEOs and founders as we are thinking about our future investments.”

The firm doesn’t focus on gender-equity quotas, she said — it invests in great ideas. And those great ideas often come from, and are best executed by, founders who are trying to solve problems they have faced on a daily basis.

“We find in education that there is a tremendous amount to be said for having experience,” Nelson said. “You have to understand their pain points. You have to understand their limitations and how they think about purchasing decisions.”

She is careful to caution, however, that raising venture capital is not the only path an ed-tech startup can take to grow and scale. Companies that have worked to bootstrap their growth, are able to build resilience and stay lean, which can ultimately help build a stronger, more sustainable company for the long haul, she said.

Meeting customers’ needs and bringing in revenue should be the top priority, followed by building fundraising to support those objectives, she said.

“Raising money should never be the goal,” she said. “It should be in service of the business that you’re trying to build.”

The Teacher-Entrepreneur Pipeline

Emily Foote knows the teacher-to-venture capital pipeline well.

The partner at Osage Venture Partners, a Philadelphia-based early-stage VC firm focused in part on the education space, grew up just a few blocks from City Ave, a main traffic artery in Philadelphia and a visually jarring dividing line between the city’s wealthy Main Line suburbs and its most under-resourced neighborhoods.

The disparity between the education she received in the suburbs, and the lack of opportunities for friends just a few blocks away drove her to pursue teaching, where she saw up-close the mammoth issues schools were wrestling with every day.

Looking to address those issues on a broader scale, Foote earned a law degree and started practicing special education law. At the same time, technology was advancing at a pace where she could see the potential it held to address some of the more intractable issues she encountered as a teacher.

In 2011, Foote began working with a former professor of hers from law school who had begun developing a video-based microlearning and assessment company with help from a Small Business Innovation Research grant from the National Science Foundation.

There’s a principle we like, of wanting to back business builders that have lived the problem, and so many women live the problems we see in education.

Emily Foote, partner, Osage Venture Partners

The co-founders ultimately raised more than $1 million in SBIR grants over multiple rounds to fund the startup, then called Practice. (It was originally founded as AppreNet.)

Her experience in the classroom was invaluable in building the product, she says, something she sees often in companies founded by former teachers.

“There’s a principle we like, of wanting to back business builders that have lived the problem, and so many women live the problems we see in education,” Foote said.

Practice went on to raise more than $8.3 million in seed, Series A, and bridge funding rounds. It was ultimately acquired in 2017 after receiving an unsolicited offer from Instructure, which Practice had initially reached out to as a potential investor in the bridge round earlier that same year.

Foote’s success in fundraising and selling the company came with its challenges, including those commonly experienced by women.

Prior to raising one of their rounds, Foote confided in a seed investor and mentor that she was pregnant. The investor, a woman, was quick to tell her to not mention the news to potential investors.

Foote, not wanting to put her team or fundraising efforts at risk, followed her advice. Ultimately, the investor the company negotiated a deal with provided a level of support that was “wonderful,” and was aware of the pregnancy before term sheets were signed, Foote recalled.

Now, as an investor, she faces different dynamics, including being one of the only people on her team without an MBA or a financial consulting background, both of which are common in the VC world.

She tries to lean in on her distinctive strengths and push beyond her own, preconceived limits.

“I have to remind myself to not try to assimilate to other people’s strengths, so that I feel comfortable in a room of sameness when I’m the other,” she said.

Building Their Own Networks

Instead of trying to break into the old boys club, Foote and other women in the ed-tech investing space have worked to establish their own: ElleCap.

ElleCap is a network of women in the education investing space who gather with the sole purpose of scaling impact for the companies and entrepreneurs they work with, said Foote, who has helped organize ElleCap.

It was founded out of an informal gathering at the ASU+GSV Summit, and has grown to an organization of more than 200 people who get together at industry events to network, share ideas, and build business opportunities.

Networks are “a huge part” of being successful in securing investment, she said. ElleCap has more than delivered a return on the time she’s invested into it. Through people she’s met in the group, she’s secured deals, connected her portfolio companies to growth investors, and received valuable advice and support.

Join Us for EdWeek Market Brief’s Virtual Forum

Join our virtual forum June 10 & 11, 2025, to hear directly from school district leaders and industry peers about important trends playing out in the sector—and the support school systems need from education companies.

The women who belong to the group “expect nothing back but will help each other,” Foote said. In a “very competitive industry,” it’s a network that delivers “expertise to lift each other up.”

Deborah Quazzo, managing partner of GSV Ventures, came up in an era where, for women entrepreneurs and investors alike, there just “really wasn’t a lot of mentoring,” she said.

Her instinct, and that of many women in the education sector, is to be helpful and promote others who are trying to clear the same career hurdles that they once did.

“Certainly we see in education there’s a very natural tendency of the community to mentor each other and support each other,” Quazzo said. “And there’s a lot of sisterhood.”

For her, the clearest way for women to succeed as founders and ultimately make a jump into investing if that’s their goal, is to build successful companies.

Growing and scaling a startup in the K-12 space has never been easy, she said, and current market conditions make the task even more arduous. But the successes she has seen have come because women founders and leaders delivered results for their investors.

“I think equality comes with returns,” she said, “and returns are hard in education.”

Bickerstaff, the ed-tech CEO who previously ran the Australian startup, is trying something new with her latest venture.

After leaving Australia and her CEO role in 2022, she spent six months traveling before diving back into ed-tech — just as generative AI was beginning to shape industry.

Her new company, AI for Education, grew from those efforts and is currently focused on providing professional support to districts on generative AI, including creating policies and professional learning plans for educators.

The company landed its first paying district customer in June, and has since worked across 33 states, and has helped co-write AI guidance for Chicago Public Schools and Houston Independent School District. Its website offering free AI professional tools for districts and educators is approaching 1 million organic visits this year.

Bickerstaff, influenced by her previous fundraising attempts, has been intentional about not seeking outside investment, at least for the moment.

For now, she doesn’t have to. AI for Education hit $100,000 in revenue on bootstrapping this year — technically turning a profit as she and her co-founder delayed taking a salary — and are in the black for the year. The launch of their first business-to-consumer product, a virtual train-the-trainer module, was so successful they had to close registration after eight days.

“We have no external, competing priorities, and also none of the nonsense of raising,” she said. “To control your destiny as an entrepreneur, especially a female entrepreneur, is a really positive thing.”

Her boss, for now, isn’t an investor, she said –- it’s teachers and students like the ones she taught in the Bronx.

Leave a Reply